“Everesting”. An epic activity, and this blog post has ended up being fairly epic in length too, quite possibly taking longer to complete than the actual Everesting itself...

"Everesting". Climbing the height of Mount Everest (8848m, or 29,029 feet) on a bike, in one go. Intriguing. Quirky. Unusual. It has become very popular this year with coronavirus restrictions meaning no racing this summer. People are looking for some sort of a challenge to work towards and achieve. As with most things, there’s a bit of a bandwagon now and “Everesting” is now regulated by an organisation called “Hells 500”. They set rules for it – you have to complete it in one go, on a single hill, climbing and descending the same hill over and over again until you achieve the altitude. They approve your ride, and they put you in an online hall of fame, and then you can spend a fortune buying their Everesting kit…

They

say: “The concept of Everesting is fiendishly simple. Pick any hill, anywhere

in the world, and ride repeats of it in a single activity until you climb

8848m.” No sleep is allowed. The droplets in the official logo below represent blood, sweat and tears. I'd have added a fourth droplet to represent bike lubricating oil. Hopefully no blood is spilled in an Everesting attempt...

All summer long, much like cycling’s hour record about 7 years ago, Everesting seems to have exploded in popularity. I’ve watched the world records fall, and fall, and fall again. One guy broke the record, only to have it invalidated by Hells 500 because it didn’t meet the regulations, and he went back out soon after and did a “legal” record. Former pro cyclist (and dodgy steak consumer) Alberto Contador took the record, and I thought this would take some beating – a former pro would have had access to the best equipment, good roads and a good support team.

Then

a “relative unknown” from the north of Ireland smashed the record by almost 20

minutes, a huge gain. Rather than on a busy Alpine climb, he did it on a small

country road in the middle of nowhere in the far north of Ireland. He had a

support team who were probably able to informally close the road and hand him

the food and drink he needed. He stripped his bike down to the bare essentials:

3 gears, chopped handlebars, no excess weight. The road, with its 14% gradient,

was perfect – steep climbs mean you can gain the altitude quicker, and

completely straight meant no braking on the descent. Good for him. I wonder how

long his record will stand for. The females as well were putting in some

serious efforts. The record stood at about 10 hours, before being lowered

significantly. Current record holder Emma Pooley wrote a much better blog than me about her Everesting:

https://cyclingtips.com/2020/08/an-exercise-in-pointlessness-emma-pooley-on-her-world-record-everesting/

I

remember back years ago, when mapping routes on the internet was a fairly new

thing. There was a website that you could use to plot your route on a map, and

it then gave you an elevation profile for the route, and an estimate of height

climbed. Then Garmin and Strava and mainstream GPS (and heart rate monitors and

power meters) came along and all of a sudden you could have a whole raft of

data about your bike ride (or run) at the click of a mouse.

I

also remember back many, many years ago, climbing mountains in Donegal and

Scotland. These mountains might have had 600-1000m of elevation. I remember

thinking you’d need to climb these mountains 10 times over to make the height

of Everest. The difficulty in actually climbing Everest, as I found out later

when I travelled to and tried to exercise at altitude, comes with the harsh

conditions – the weather, the cold, the altitude, the lack of oxygen. But, I

had always thought it would be an interesting thing to try to climb the height

of Everest on a bike, in a single bike ride. I’d also thought it would be good

to manage to do a 200 mile ride, and wondered if the two could be combined.

So,

for years, Everesting had been in my head, but I’d never really been able to do

anything about it. I was always busy training for goal races, and doing an

Everesting wouldn’t have helped in trying to achieve what I wanted to achieve

from my goal races. I didn’t think Everesting would be good Ironman training,

and I wasn’t willing to risk trying it and setting my training back weeks if

recovering from it took a while. But this year was different. I really wanted

to try to win the world sprint triathlon championships, and I had invested a

lot of training and thought into this. Then it became obvious it wasn’t going

to happen, then it was finally cancelled. I had developed decent bike fitness

and with no other target races on the horizon, I decided I would give

Everesting a go.

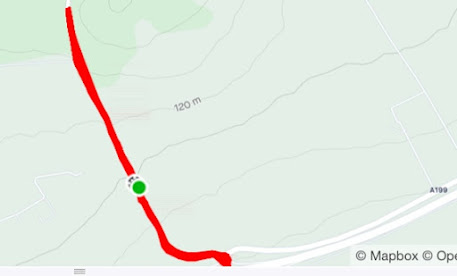

I

thought of all the hills I knew nearby. I spent a fair bit of time on Strava,

google earth and google street view, scoping out various potential hills. I

wanted a straight hill, with a good surface, with no side roads on the hill to

minimise the risk of cars pulling out. I decided on the Garleton Hill, just

outside Haddington in East Lothian. It’s also apparently locally called “the

Yak”. I knew it reasonably well. I visited it a good few times to train on it,

and get some power, heart rate, elevation and ascent/descent time data.

The

full climb was just under a mile long, with just under 100m of elevation gain.

I could power up it in just over 4 minutes at just under 400 watts, or I could

ride easily up it in 7 minutes at 200 watts. I could descend in around 2:20.

Near the top, the road flattened out before a final steep kick to the summit.

The “wee” climb (79m elevation), which removed the flat section near the top

and removed the steep summit kick, took me 3:30 at just under 400 watts, or 6

minutes at a much easier 200 watts. The wee descent took about 2 minutes. I had

to decide whether to commit to the wee climb or the full climb. In the end, I

decided that Everest was about climbing to the summit, so I would do the full

climb.

There

was a small roundabout at the bottom, so I also had to decide whether to do a

dead stop and a U-turn just before the roundabout, or whether to carry on

around the roundabout. The dead stop and U-turn would save time, but would lose

a few feet of climb, and would require very heavy braking. Going around the

roundabout would require much less braking and take a bit longer. I decided

that, because I wasn’t intending to race this, I was simply intending to

complete it, that I would go with going around the small roundabout – I would

save wearing out my brakes and rims, and would add a bit of extra distance each

time (I had an eye on this being a 200-mile effort).

I

then had to create new Strava segments for the climb and descent, because as

far as I could tell from my photographs and from Strava and satellite imagery,

the existing segments weren’t completely accurate in where they started or

finished. This is important because you need to make sure you complete the

correct altitude or the attempt will not be verified/approved. Using maps and

contour lines, I was able to determine, as accurately as I could, that the

total elevation was 95 metres (312 feet).

The

average gradient was just over 6%. The climb was fairly flat at the bottom,

then it went through a wooded section where the gradient kicked up, before

stabilising up to the flat section (which wasn’t “flat”, it was still climbing,

but at a much lower gradient), and then a final very steep kick up to the

summit. Most of the climb was at around 7%, with the steepest sections being

probably 12-13%.

I raised my handlebar stem - usually it's as low as it can go, to get me lower on the bike (and therefore more aero and faster). But for the Everesting attempt, a higher and more upright position would be of benefit if I was going to be in the saddle literally all day...

I wondered about my gearing. Going up the climb at what I thought was a realistic Everesting pace (which couldn’t have felt any slower to me as someone who enjoys and is reasonably good at powering up hills at full speed), meant I was doing about 200 watts at around 70-75rpm in my lowest gear (34-28). This is quite a low cadence and I wondered about getting lower gears to be able to spin more easily up the hills, reducing load on my knees. To do this would have meant buying a new cassette and I would have needed a new longer derailleur too, to accommodate the bigger sprockets. It would have needed a mechanic to change everything over and all of this meant I decided against it. I’d make do.

I

was then able to make a spreadsheet. To do an Everest would require 94 climbs

(and 94 descents). I rounded this up to 95 to be sure. This would total to 184

miles, or 296km. Both annoyingly short of the 200 mile and 300km milestones.

And also, 95 climbs is annoyingly short of a nice round 100.

You

can choose to carry on and complete 10,000 metres of climbing. This would

require 106 climbs (rounded to 107), which would easily break the 30,000-foot

barrier, and the 300km barrier, and the 200 mile barrier. So I decided that my

target would be 107 climbs.

From

my “training” on the hill, I anticipated that my climb time would be around

7:20 and my descent time would be around 2:24, giving a total “lap” time of

just under 10 minutes. So I could hope to complete 6 ascents per hour. This is

when I realised it would be a much longer day that I had ever anticipated… This

would mean that “Everesting” would take nearly 15 and a half hours (longer in

reality, because I would be largely unsupported and I would have to have quite

a few stops to pee, to top up my food and drink, to change my clothing

according to the temperature, time of day, and darkness levels). 10,000m-ing

would take nearly 17 and a half hours in the saddle (again longer in reality

with the breaks/stops I’d need).

I

had hugely underestimated this. I saw that the male and female record times

roughly corresponded with top-class Ironman finishing times, and I thought that

Everesting would roughly correspond with my Ironman finishing time (just over

10 hours). How wrong I was…

Perhaps

if I was able to strip my bike down, minimise weight, train specifically for an

Everesting, find a support crew willing to stand there all day and hand me food

and drink every lap, and have people warning traffic, then I could go faster,

but this was a completion endeavour, not a racing endeavour, as I had to keep

reminding myself. It was looking like a long day.

And,

to be fair, I wanted a long day. I wanted to be challenged in ways I had never

been challenged before. I wanted to hit a point where everything was screaming

at me not to carry on, and yet I had to force myself to continue, to make the

distance and elevation. I wanted to be “into the unknown”. My Ironman races

have not really been “into the unknown” – I trained specifically for them and

never had any qualms or nervousness about the distance. I knew I could do an

Ironman. Everesting felt a bit different.

Yes,

I had been cycling this year, for months, often 6 times per week. But I hadn’t

trained specifically for an Everesting. Many people do a “base camp” before

they do an “Everest”, where they do half the elevation, they see how it goes,

they learn from it, and they are better-placed to go on and do an Everest after

that. I wanted to get straight into the Everesting and challenge myself.

I

did want to put a couple more hundred-mile training rides in my legs before

trying the Everesting. Two rides in particular stand out. For most of the early

part of the “season”, I was doing all my outdoor rides on my heavy hybrid

commuter bike. This actually worked well, as it helped put strength in my legs,

and allowed me to “just ride” without worrying about power and heart rate. One

ride on this bike turned into a 100-miler. I never thought I’d do a ton on the

hybrid. It felt great when I was doing it, but I didn’t have enough nutrition

or hydration as I only intended it to be a 50-miler. So I was completely wiped out

for a good few days afterwards.

Another

ride (on the road bike this time) was out in the Lammermuir hills. There’s a

good loop out to Duns, which I have been wanting to do for a long time. It’s

quite remote, and very scenic. I knew there were a few good climbs out there

which I wanted to suss out, to see if they were viable Everesting options (they

weren’t – too far away, too remote, roads too narrow, and too steep). I did the

loop to Duns and back with a friend. A grouse flapped straight into his front

wheel at 30mph – I don’t know how he stayed upright. I felt great after our

70-80 hilly miles. I was pushing pretty hard on the climbs. One on particular

is quite well known – “the Rigg”. It kicks up to nearly 20%. I was hitting 600

watts going up it (nearly 10 watts per kilo), and I was pushing other hills

similarly hard. By the time we had finished, I was still feeling good and

decided to carry on to put 100 miles in my legs.

So

I headed for Haddington and my Everesting hill, to do a few more repeats. I did

a mix of high and low powered ascents and was still feeling good, so I thought

I would carry on to hit 200km. So I headed north to the coast, and then back to

Edinburgh along the flat coast road. I was still feeling great and powering

along the coast road. I got back to Edinburgh and was still feeling great to I

went to Arthur’s Seat and hammered out a climb there, and was able to hold well

over 300 watts for around 4 minutes. I was at a good fitness peak at this

point. Not long before this ride, I had hit 326 watts at 62kg for 20 minutes on

the turbo trainer. I was in good shape. Good cycling shape anyway. I came off

this 200km+ ride feeling really strong.

But

if I have learned one lesson from this year, it is that you do not need a big

performance in training to prove that you can do a big performance. Big

performances in training actually hinder the upcoming training consistency. Big

performances should be left for the races, and I must be more aware of this in

future. Be fresh and strong for the races. Don’t over-train and lose 2 weeks

because the training was too hard or too long. Trust in the training. After my

100 miles on the hybrid, I was wiped out for a week. After the strong 200km

hilly ride, I was even more wiped out the next day and it took a good few days

to feel normal again.

Another

thing that wiped me out around this time was my first run for about 3 months. I

had been struggling with niggles and poor performances and low motivation for

running earlier in the year and when lockdown started, and with nothing to

train for, I decided I would give myself a break from running. My first run

back was part of a club “dawn-to-dusk” virtual relay for a local charity (which

I then wrote an article about for the paper!). It was an easy 30 minute run, about

4 and a half miles, half of which was on grass, and my muscles were in agony

for days afterwards. I had fitness but no running muscle conditioning

whatsoever, and it felt terrible. I’ve tried to get back running now once a

week to maintain some semblance of muscle tone and conditioning, so that when I

do start training/running a bit harder again, the muscles will be ready for it.

That’s the longest I’ve been without running for a very long time.

It

was the same for swimming. I spent months using swim cords in my flat to try to

replicate swimming, and finally did a couple of open water swims. Loch Lomond

was relatively “warm”, Loch Morlich was a lot colder. It felt good to swim

again, but the hassle of open water swimming (driving somewhere, taking ages to

put on the wetsuit, being a huge wimp in the cold, limping and stumbling barefoot across jagged stones to get into deep water, not wanting to come across

any water beasts, jellyfish etc, then having to get changed again when freezing

cold, then wash out the wetsuit and get it dried, all of these things mean I

don’t swim in open water all that often. Give me a nice benign swimming pool

any day…!

For

the Everesting ride, I had to buy an external battery pack and charging cable

for my Garmin bike computer. You have to record your ride and upload it to

Strava online for official verification. My Garmin is quite old now, and on my

longest ride (last year, 9 and a half hours), it went from 100% charged to 20%

charged. It wouldn’t last as long as an Everesting would need it to. The

battery pack was easy to source. The cable wasn’t.

When

you plug a Garmin into a computer, a 2-way flow happens: it charges (i.e.

charge flows “into” the Garmin), while simultaneously, data flows “from” the

Garmin to the computer, to be uploaded to whatever online platform you choose.

This works fine when the Garmin isn’t being used to record data as on a bike

ride. When the Garmin is in use on the bike, recoding data, plugging it in to

charge causes it to freak out and shut itself down. Which means you lose all

the data. So, 10 hours into an Everesting attempt, I didn’t want to plug it in

to the portable battery pack which would be in a top-tube storage pouch on my

bike, and have the Garmin shut down, losing all 10 hours of data… In case of

any mishaps, I planned to take photographs of my Garmin display screens periodically

during the ride so I would at least have some proof. But I did want to the

whole ride to record without any trouble.

I

needed an “OTG” cable (On The Go) which has one of the connecting pins removed,

which “tricks” the Garmin into thinking there’s no need to transfer data from

the Garmin into whatever it is plugged into. I went onto eBay and spent a few

quid on an “OTG” cable. I trialled it while on the turbo trainer. I plugged it

in and boom, the Garmin shut down. I tried again. Same result. The cable was

rubbish. I did some googling. It seems that sellers don’t often know what does

and does not constitute an OTG cable. You can do a bit of DIY with a soldering

iron, to take one of the connecting pins out of action. But I didn’t have a

soldering iron, and I wanted the correct item. So I called up a couple of local

electrical stores. In the end, I brought the Garmin and battery pack to one of

the stores and tried the cable out in person. It worked. Relief.

So

I set a date for Everesting. It was to be the week before a short “staycation”

up in the Cairngorms, where I had worked for a couple of summers many years

ago. I wanted to get it done before the break, so that I could have something

to show for the year and so that I could try to relax and enjoy the break,

climb mountains, go on the mountain bike, go trail running etc, all without

worrying about having to train and without worrying about the often-injurious

impact that doing anything that isn’t swimming, cycling or running has on my

body.

The

weather forecast continued to look good (I would have called it off had the

forecast been bad), and I went shopping the day before to stock up on food and

drink. I had no idea what I would want to eat and drink during the attempt, so

I tried to cover every eventuality. Suffice to say I spent a lot of money. In

addition to the energy gels, energy sweets and Tailwind drink mix, I bought all

manner of cereal and energy bars, all manner of fruits and nuts, all manner of

cakes and biscuits, all manner of ingredients to make “real food” wraps, all

manner of anything and everything I could possibly think of that I might

possibly want to eat. And I bought some emergency Coke and did what I could to

flatten it. Oh, and I bought a few 1.5 litre bottles of water. 18 of them. I’d

have about 30 litres of liquid in my car, including some pre-mixed Tailwind

drink.

Then I brought all this back to my flat and packed it into a huge box. I packed a pile of gear into another huge box. Again I covered every eventuality. Spare shoes, multiple spare socks, leggings, tops, gilets, jackets, all manner of reflective gear, lights, glasses, suncream, gloves, hats, towels, sanitiser, toilet paper, kitchen roll, salt, tools, puncture repair stuff. Everything I thought I might possibly need. Probably well over half the contents of my flat (well, nearly). And I lugged it all down into the car. With help from my girlfriend. Several trips back and forth were needed to pack everything.

Everesting (or at least, an attempt on Everesting, which I wanted to be 10,000m-ing) would be the next day. I was excited. I was a bit daunted, which I wanted to be. It felt like very much into the unknown. Into the abyss. I had trained a lot on the bike, but I hadn’t really done any specific training for Everesting. I’ve never really felt daunted by an Ironman because I knew I’d done the training and knew I could do it. This was different. I had mulled over starting off with doing a half-Everesting or “basecamp” effort, but I figured I would probably be able to do a half-Everesting without too many issues. I wanted to be tested and to find physical and mental limits, and I didn’t think a half would do this. I just wanted to get out there and ride and see how it would go. I had told a couple of friends, who had said they would try to ride out to the hill and do a few repeats with me at various times of the day.

So

it was all set. I wanted to have started by first light, which would mean

getting up at 3:20pm, to try to be started well before 5am. That should give me

almost 18 hours of daylight. I went to bed shortly after 8pm. And

frustratingly, I just could not get to sleep. And the later it got, the more

frustrated I got, and the more frustrated I got, the less likely it became that

I would get any sleep. It was strange. I don’t usually have problems sleeping.

I

remember in 2005 when I was working in the Alps, I had a couple of days off. I

had rented a road bike. I had planned to get up early, take the first train

towards the base of Courchevel, do the Courchevel climb, descend down, and then

climb up to the Col de la Madeleine, descend down the other side and get

another train back to where I was staying. This was a big day of cycling,

comparable to a Tour de France stage, and back then there is no way I would

have considered myself a cyclist. I was pretty excited, and a bit daunted. I

couldn’t sleep the night before this ride either. I went and did it anyway. The

Courchevel climb went fine, the descent was scary (I was overtaken by a proper

cyclist who obviously knew the road and I tried to keep up with him but didn’t

have the bottle for it), then the climb up the Madeleine was horrendous, my

knee got sore, I got to the top of the Madeleine, I was going to be very tight

for the last train home, and the descent was horrendous. Everything hurt. My

arse, my hands, my arms, my shoulders, my back, my legs. I don’t know how I got

down. I made the train by about 2 minutes…). Everesting would be a much longer

and tougher day than this…

So my 3:20am alarm went off on the morning of Saturday 18th July, and I hadn’t slept a wink. I got up, looked out, and it was already starting to get bright. It was decision time. I bailed. I decided I needed to have slept before such a long day in the saddle. I went back to bed and slept terribly.

I

tried again for the following day. Another early night. Surely I would sleep

now, given that I hadn’t slept the night before? And, same story. No sleep.

What was going on? I bailed again. I was gutted. I couldn’t believe that I

couldn’t sleep. I vegetated in bed for most of the rest of Sunday. I had to

empty the car. I wouldn’t be trying again any time soon, as the staycation was

booked, my first day off work was in 5 days’ time. I felt I had hit a physical

peak a few weeks back with a good 20-minute FTP test (nearly 5.3 watts per

kilo) and a very strong long bike ride. I felt that since then I was fighting a

bit to try to maintain fitness, and it did feel like I had peaked and gone over

the crest. At this point, after bailing twice on an Everesting, I felt like I

was well past my mental peak as well. I had felt like I needed a break from

everything, and doing an Everesting would have given me the chance to do this.

I couldn’t really cancel or re-schedule the holiday because I had to have taken

the leave by the end of July, and I didn’t want to write it off.

So

I had a couple of weeks where my diet and training slipped a bit, and I put on

a bit of weight. I did enjoy the break in and around Aviemore and the Cairngorm mountains. It's a fantastic place, and there's so much to do there. It is difficult to believe it has been 16 years since I first went there to work during summer 2004, and again in 2007. Activities included some fantastic mountain biking up to

Loch Einich, some great trail running around Loch an Eilean, some canoeing and

swimming in Loch Morlich, and some really scenic and hot hillwalking on Meall a

Bhuachaille and down to Lochan Uaine. All of these did lead to legs, knees and ankles that were a bit sore, and I had to hope they would feel better quickly because Everesting was still very much on my radar. I wanted to achieve something in 2020...

It was then into August, and the daylight was starting to rapidly drop away, losing 5-6 minutes per day. If I was going to do an Everesting, I would need to hurry up. So I put in a 4-hour ride to test my legs/knees/ankles, and then a higher-powered turbo session. Everything felt OK enough to decide to go for an Everesting on 8th August. Most of the gear was still lying in the big boxes on the table in the living room. I went food shopping again, went through all the preparation and build-up, got everything ready. More wraps were made by my girlfriend. And again I went to bed early. I knew a colleague and friend from work was attempting the “Bob Graham Round” (100km+ of fell running in the Lake District, climbing 42 peaks with a total of 8200m elevation) at exactly the same time as I’d be Everesting. We had chatted a bit about the respective endeavours and said we’d have a debate in person when they were over, to discuss which one is toughest.

And,

once again, I couldn’t sleep. I was less “agitated” about it this time around,

and although I didn’t sleep, I did feel a bit more rested. 3:30am came. I could

delay another day, until Sunday, but I’d probably have the same issues again.

Plus, I didn’t want to be back in work 8 or 9 hours after an Everesting, I

wanted to have a day to recover without any obligations. I could delay it

another week or two, but there would be even less daylight. And, I was getting

fed up with this. Completely fed up. The whole build-up. I wanted it done. My

friend and cycling buddy Kev hadn’t given me much sympathy after the failed

attempts, and neither did I want sympathy, but he had simply given me a verbal

boot up the arse, saying “Just get it done…” I had to get out there, get on the

road, and see how it went. So I got my porridge, got kitted up, and got on the

road. It was a 30-40 minute eastward drive to the hill.

It

was still dark, but there was a faint glow of light away off to the north-east.

I hadn’t planned to use lights at the start of the ride – I had tested them and

the brightest setting on the front light only lasted an hour and a half. Plus I

didn’t want to be stopping after half an hour to remove them, not wanting to be

carrying any excess weight.

I

arrived to the hill. There is a small water works about a third of the way up,

and it had a small lay-by. There was just enough room to reverse the car into

it. I got set up – got the bike out, arranged the boot of the car, put the rear

seats back up (they were down to transport the bike), and made sure there was

no gear visible when the boot was closed. It was only just about bright enough

to get away without using lights, but I had on reflective trousers, a high-vis

jacket, a reflective helmet, and also a pair of gloves under my cycling gloves,

and a hat under my helmet – it was chilly in the early morning and I could see

my breath.

I

manually calibrated my Garmin to the correct altitude. From various maps and

contour lines, I reckoned my “base camp” (i.e. my car) was at 321 feet

altitude. So I set the altitude at 321 feet. I knew from analysing various maps

and contour lines that each ascent would be 95m, or 312 feet.

I had to get going. There was no pomp or ceremony or anything. No-one there. I didn’t mind at all. I recorded a quick video and freewheeled off down to the bottom of the hill. Everesting was finally underway…

I

could probably write the rest of this blog post quite quickly, because the time

passed quickly – much faster than I thought it would. Actually getting to the

start of my Everesting was much tougher than I thought, and it seems I had a

lot more to write about getting to the start line than I anticipated. Basically

I climbed and descended a hill 100 times on a bike and successfully

“Everested”… But, I will try to do it some justice.

I

had chosen to go around the small roundabout at the bottom of the hill. The

gradient eased a lot at the bottom of the hill, on approach to the roundabout.

So, I thought that I could stand up on the bike and make myself as big as

possible on approach to the roundabout. The increased frontal area and

decreased gradient would help to slow me down without needing heavy braking.

Repeated heavy braking is very tough on the arms, hands, wrists etc, and after

a while it can become difficult to modulate the braking and pull the levers

hard enough. I didn’t want to have any issues with difficulty braking, nor did

I want to wear out my rims and brake pads. I knew going around the roundabout

would add a bit of time, but it would also add a bit of distance, and I had an

eye not only on Everesting (8848 metres of ascent), but on getting to 10,000

metres of ascent, and not only this but on completing a 300km ride, and if I

was going to do 300km then I may as well continue to break 200 miles…

This

worked well, and with a fairly baggy jacket, when I stood up on approach to the

roundabout, my speed ebbed away. On final approach, I needed a brief squeeze of

the brakes to get to a speed where I could stop if I had to. One look to the

right to check for oncoming traffic (more often than not there was no traffic)

and I was onto the roundabout, and then looking left to make sure any traffic

looking to join the roundabout had seen me (again more often than not there was

no traffic). Then it was a case of getting round the roundabout without banking

too hard and risking skidding. The surfacing was fairly decent, but I soon

noticed a feather right on my line, and I had to avoid it each time to avoid

losing traction on it when banking. On the exit of the roundabout was some rougher

road and I always missed this to the right, keeping me nicely in the middle of

the road and hopefully more visible.

Then

exiting the roundabout, I beeped my Garmin to signify a descent completed and

it was onto the climb. I got to know the climb pretty well… it was initially

westbound on a gentle gradient, with a gradual curve to the right, to become

pretty much northbound. There wouldn’t be much wind, and it was going to be a

cloudless, hot day later. The car was very conspicuous. The early part of the

climb was through a tunnel of trees, but the road was fairly straight with good

visibility. I had picked the road with safety in mind. Aldo, there were no side

roads, so nothing would pull out into the road in front of me.

The

gradient ramped up to one of its steepest sections just before I passed the

car. Then it was onwards and upwards. Just beyond the car was some “road art” –

a big pink heart painted on the road, with “LO” written under it in big letters.

I had no idea of the significance of this – I’m pretty certain it wasn’t

specifically for me. I said I’d get a photo of it when I got halfway through.

The trees on the left gave way to a stone wall and corn fields beyond. Back

over my left shoulder was a view westwards towards the Pentland Hills, and

Arthur’s Seat was even visible at times. It was a fairly steady gradient at

7-8%, onwards and upwards, the trees on the right then gave way to a wild

meadow, beyond which was a rocky crag. Near to the top, the road flattened out.

I had debated turning at this point, but then thought that climbing Everest is

about getting to the top, so I decided I would complete the full climb. The

short, flatter section allowed a change of gear and a brief spin of the legs

before the road ramped up to its steepest gradient for a short, sharp stinger

up to the crest.

Approaching

the crest required a look behind to see if there were any vehicles behind (usually

there weren’t). At the summit I had to look to see if any traffic was

approaching. If there was traffic, generally I just signalled that I would

stop, and I let the traffic clear before making the turn, beeping my Garmin to

signify another ascent complete, trying to look at the ascent time and the

number of laps complete, and setting off on the descent.

The

descent was initially steep enough to get up to speed quickly, so I usually

gave a little bit of a kick for maybe 10 seconds to get up to speed quickly,

and then I was able to freewheel all of the descent. This allowed my heart rate

to come down, and allowed my legs to recover. The mind was alert on the descent

however, as I was usually hitting over 30mph. You need to be alert at 30mph on

a bike. I could probably have raced the descent faster, but I was happy enough

taking the recovery, shifting weight off my backside and maintaining a speed I

was comfortable with. The first few descents were a bit more cautious before I

got used to it. As I approached the roundabout, I was able to stand up and

stretch out as much as possible, while scrubbing off speed before reaching the

roundabout.

I

figured it would take a few repeats to get into the swing of things and get

warmed up. There was no rush on anything. There was no reason to force

anything. I knew it would be a long day. The goal was to complete it. I wasn’t

racing. Neither was I messing about and wasting time. I just went about the

business of trying to be as efficient as I could. But it was difficult to know

how hard (or rather, how easy) to ride the climbs. I didn’t want to go too hard

too soon and then risk blowing up and running out of energy, or having my knees

give up on me, or end up vomiting and diarrhoea-ing. Earlier in the year my

fitness had peaked with a 326-watt, 20-minute effort, at 62kg. Approaching

Everest, I was slightly less fit and slightly heavier, I would guess 315-320

watts for the 20-minutes, and 65-66kg. For an Ironman (5-6 hours depending on

the course) I can average around 190-200 watts.

For

the Everesting climbs, I seemed to settle in to around 7:20 pace, at around

190-200 watts, and a heart rate of around 125bpm. I guessed that the pace and

power might drop later in the day as I fatigued, and as the temperature

increased. I figured my heart rate would likely increase too. But for now, it

felt OK. Several times I had to check myself and ease back. 80-85rpm would be

220-240 watts, so I had to drop back to 70-75 to get back below 200 watts. It

was all about capping the power and heart rate now, so that things wouldn’t

become unmanageable later.

I had to make sure to eat and drink regularly. The first, flatter part of the

climb was a good opportunity to do this, when my heart rate was low after the

descent. I had no idea how my body would react to food and drink on such a long

day, or what I would want. I had tried to cover all the bases, with a vast

range of food in the car. I generally carried enough for up to 2 hours before

needing to stop to replenish. I developed a vague strategy where I would have

water with gels, energy sweets and energy bars on the bike for a couple of

hours. Then I would stop, eat something more substantial (a wrap, a bit of

cake, a few jaffa cakes, a swig of flat Coke), wash it all down with water, and

then for the next two hours I would give my stomach a break by consuming only

Tailwind (energy drink). Then I’d stop again, eat something more substantial

and switch back to water/gels/sweets for the next two hours.

I

knew from previous visits to the hill that my total ascent plus descent time

could be around 10 minutes, giving me 6 full laps per hour. I needed 94 laps

for Everest (which I rounded to 95 to be sure), and 107 for 10,000m. 6 laps per

hour meant an Everesting would take nearly 16 hours (more with stops), and a

10,000m ascent would take nearly 18 hours (more with stops). I found that my

ascents were taking around 7:20 and my descents were actually quicker than I

thought, at around 2:20, giving a total lap time of 9:40. So, it was what it

was. I just had to ride and get the miles in and see how it all went.

I

had noted that when passing the car, the altitude wasn’t 321 feet as I had set.

And I had also noted that the Garmin was recording slightly more than 312 feet

per ascent. So there was a little bit of a calibration error, which isn’t

uncommon. I had done the background work however, and I knew that my 95 climbs

would get me the required altitude of Everest, plus a little bit extra. It was

just that when I achieved it, my Garmin would say I had done more than I

actually had.

During the first hour or two, I felt very tired. Swallowing feels different when you’re tired. The inside of your mouth feels different. Food and drink feel and taste different. It was a strange feeling. I hadn’t had any sleep. I wondered would I feel more and more tired as the day went on, and what I would do about it. The first milestone of the ride came at 5:48am, when I first glimpsed the sun through the trees to the east.

The second milestone came when I first needed to pee. There was nowhere good to pee anywhere on the climb. Behind the car wasn’t great, as oncoming traffic could see. At a random spot at the side of the road wasn’t practical as traffic could see, and your backside would literally be in the road. On the flatter section near the top, there were a couple of makeshift lay-bys – very small stony verges. But again you were very visible there, and I didn’t like being on stones in my cleated shoes, as I didn’t want the cleats to get damaged. There was a small trail running from one of the lay-bys so the best thing was to walk a little way down the trail and get out of sight. It all took more time that I would have liked however.

And,

as much as I thought it was the best and most discreet place to go, on one of

my first toilet stops, I was mid-flow when I heard heavy breathing. An

early-morning trail runner had come from the rocky crags on the other side of

the road, and was now standing by the road, watching me. A lady. She obviously

knew I was peeing and didn’t want to run past me, but rightly didn’t want to

stop her run either. I just had to say “sorry, quick pit stop” which kind of

broke the ice (you’d imagine trail runners are used to wild peeing) and she

laughed and ran on.

12

laps passed in just under 2 hours. It was time for a quick “base camp” stop at

the car, to replenish. I had thought through in advance everything I would need

to do, so I wouldn’t waste any time. The first thing I did was drink about

500ml of flat Coke. I ate a couple of other bits and pieces, cleared out the

used wrappers from my pockets, swilled out my mouth with water, replaced the

empty bottle on the bike, re-filled the pouches on my frame with gels/bars, and

got going again. I still kept on my “warm gear” as I could still see my breath.

The flat Coke was fantastic, it worked a treat and I never again felt tired.

Maybe the sun coming up also helped.

I

had all manner of data displaying on scrolling screens on my computer. My

average power seemed to stabilise at around 159 watts. My normalised power was

stable at 187 watts. On the “average” sections of the climb, my heart rate was

around 130-135, and on steeper sections, it sometimes climbed to 145-150 if I

wasn’t paying enough attention, but the steeper sections were relatively short

so there was never a chance that it would go much higher. I enjoyed watching my

altitude creep upwards. I enjoyed keeping an eye on all the metrics. Currently,

the gap between “elapsed time” (which includes stops) and “moving time” (just

that – time spend actually in motion on the bike) was pretty low. I hoped it

would stay low, but if I started to really struggle and needed long breaks,

this delta would increase.

For

now, it was a case of “so far, so good”. As the temperature rose and the sun heated the tarmac, a number of black beetles and caterpillars started crawling onto the road and I tried as best I could to avoid them all. I quite enjoyed watching the sun move.

For a few repeats, it was right in my eyes at the roundabout, which meant I had

to slow right down to a crawl as I couldn’t see a thing. But three laps and 30

minutes later, it had moved enough to re-enable good vision. The sky was

absolutely cloudless. It was going to get hot. I wondered how Matt was doing on

his Bob Graham Round. As the sun rose, and the temperature increased, and the

half-litre of Coke kicked in, my tiredness dissipated and I felt more alive. So

far, so good.

At

just after 10am, after 5 hours, I had a slightly longer stop. All my pre-mixed

bottles were finished and I had to make up new drinks mixes. I ate some more

“proper” food, with a mackerel wrap providing some protein. I decided it was

warm enough now to get changed out of the jacket, gloves, leggings and hat. I

had shorts on under the leggings, and I whipped off the two tops, leaving them

to hang and dry off the front seat. I put on a long-sleeved, slightly thermal

top (I’m terrible in any sort of cold and I would far rather be too cold than

too hot, and I was a bit worried about being cold on the descent). I took off

the hat and changed into a more comfortable bright yellow helmet. I slathered

on the suncream as well. And got going again.

By

now I was well-acquainted with the hill. I knew all the bumps, knew the lines

to take. There were a few stones on the summit which were on my turning line. I

didn’t want them to cause me to skid and possibly crash, so I stopped and

kicked them out of the way. I had a bit more freedom now to use my phone to

take photos, as my fingers were now free from gloves. I periodically took

pictures of my Garmin displays, in case anything went wrong and I lost the

data. I saw a few cyclists. They all overtook me. Not much chat. I’d have loved

to have thrown off the shackles and ripped up the hill past them. I could

easily have gone at twice the power I was at, but for what? For later ruin? So

I let them go… One lone cyclist did ask me if I was having a good day on the

bike. I couldn’t resist: “I’m doing an Everest!” He just laughed and that was

the end of that. With the baggy jacket no longer flapping in the wind, my

descent times got slightly faster.

I

managed to record a short video update for my girlfriend back at the flat. She

couldn’t possibly have come out all day, but we said we would see how it went

and if I was still going by late afternoon she might try and get out for a

while in the evening.

The

colours were fantastic. Lush green, and splashes of pink, purple and yellow as

the summer flowers were in full bloom. The cornfields were also quite dazzling,

with a fantastic contrast in colour between them and the sky. The rocky

crags were catching the light nicely. And very fleetingly I would take a

look over my left shoulder, away off to the south-west, to get a glimpse of the

panorama away across to the Pentlands and the Lammermuir hills. Only fleeting

glances were possible, as I had to concentrate on the road. It was the same on

the descent. The panorama was almost directly ahead but I could hardly look at

it as I had to focus on the road whizzing by under my wheels. I wondered if I

would get bored…

The outside of my right foot, after maybe an hour of running, or a good few hours of cycling, can get very sore. When I run, I land on a very specific spot on the outside of my foot, and I have callouses which haven’t been recently treated as I haven’t been to the podiatrist during lockdown. Regular podiatrist trips certainly help. As midday approached, it flared up and got sore. I had brought spare shoes and spare insoles which I thought might help if it flared up, but after maybe an hour, it abated and never bothered me again. Maybe it was all the moving around on the bike, taking weight off my back side on the descent, and taking weight off first one leg then the other on the descent. I was relieved.

By

and large there had been very few problems with traffic or dodgy driving. One

incident was when I was descending on approach to the roundabout. The road

curves gently to the left. On the few occasions when a car was behind me, I would

signal right, move to the middle of the road, and the cars would let me

continue to the roundabout. There was no room to pass and it would have been

dangerous as they couldn’t have seen around the curve. Your ears tell you a lot

– a car came behind me, too close for comfort. It was revving and I knew

straight away they were anti-cyclist. Little boy racers. I signalled right,

moved to the middle of the road, they’d have to wait behind me for 10-15

seconds until the roundabout. And they came flying past me, in the opposite

lane, no visibility of anything. Mercifully there was nothing coming the

opposite way. Idiots like that shouldn’t be allowed to drive.

On

another occasion, again at the top, I knew there was a car behind me. There

were two other cyclists stopped at the top. I signalled to the left and pulled

in tight to the side to let the following car through. I had to clip out and

put my foot down. I checked fore and aft and there was nothing coming, so I

pushed off on the 180-degree turn for the descent. Then, all of a sudden,

something was coming, far too fast. The road is a “national speed limit

applies” road, but there’s no way 60mph is an appropriate speed. 30mph is too

fast for cresting the summit. 40mph might be acceptable on the straighter and more

open parts of the descent. This car came screaming past on the crest of the

summit at far too fast a speed, had to pull right out to avoid me and then

zoomed off down the hill. Idiots like that shouldn’t be allowed to drive. In

fairness the number of “idiot driver” cases was actually really low for such a

long day.

I made sure to try to shake out my arms and shoulders when I could, to try to keep them mobile and to try to prevent them from becoming stiff, seized and sore later in the day. At the bottom of the descent, I was able to stand up on the pedals and get my back moving a bit, and try to stretch it as well, as best I could.

The

next big milestone would be when my friend Dermot appeared. I had told only a

few people about my Everesting attempt. There were a couple who would have

cycled out for a few repeats of the hill had I managed an earlier attempt, but

they weren’t about this time. My good friend and cycling buddy Kev also wasn’t

around on this particular day. Dermot was about, and he said he hoped to arrive

on scene at about 1pm for a few repeats. So this was something to look forward

to.

I

wanted to be fully fuelled by the time he arrived, so I had another stop to eat

another wrap, get everything replenished and re-filled, and stretch my back

out. I was now coming up to 7 hours in total, still feeling decent. I had done

a few climbs out of the saddle, but had found it was easier and more

controllable to remain seated while climbing and get out of the saddle on the

descent. I was sure I would need to vacate my bowels at some stage during the

day. I started to think Dermot could “help” with this by watching my bike while

I headed into the woods. So I started to try to look for suitable places. There

wasn’t really anywhere obvious.

It

got even stranger when the guy in the car parked next to mine put his seat back

and seemingly fell asleep. At least I didn’t have to stop any time soon, I had

enough food and drink on me to get me through another couple of hours.

On

the final hill before Dermot arrived, at the top, there was dead silence.

Usually if a car is behind, you can hear it (I can’t understand people who ride

bikes with headphones in – I get so much information from my ears). On this

occasion I didn’t hear anything, and there was nothing coming towards me at the

summit. Usually following cars had to wait for the summit so they could see

ahead before they overtook. Without really looking, I made the turn and was

horrified to see a car immediately behind. How had it crept up on me so

silently? It was an older couple who weren’t likely to get abusive, but the

driver did gesture as if to say “what the hell?” and probably rightly so. I

shot him an apologetic look and was away on the descent. I would have to be

careful, particularly later in the day as I got more fatigued.

Dermot

finally arrived as I was hitting the halfway point. It was good to see him. He

didn’t really know what to do – ride ahead and pace me, or hang back and let me

dictate the pace. He wasn’t even sure if it was “allowed” that he could take

the lead. Riding beside me wasn’t really an option as it was the middle of the

day and although there wasn’t a constant stream of traffic, you’d be seeing a

good few vehicles per lap. But he knew I couldn’t compromise my riding, and

that I’d just have to continue on. And so that’s what I did.

We

had a bit of a chat. I was feeling reasonably good. My back was getting

gradually more and more sore, and my shoulder was starting to ache. I was

starting to feel the tendons down my knees weren’t as happy as they could be.

But it was all manageable so far. I was past halfway. I said at this stage it

was looking like I would be able to finish, and if I did, it would be around

9pm. But a lot could still go wrong. We chatted away. He asked if there was

anything he could do. I got him to clear a few stones from my line near the top

of the hill. He took a few photos and videos, which was great. I mentioned I

might need some help with the big toilet stop and he said he’d do whatever he

could but that I could wipe my own arse. I laughed, pointed to my back and said

well, I might not be able to wipe my own arse. He said, well, I have to

maintain social distance. I said that’s OK, put some of my toilet roll on a

stick…!

Dermot also tried to keep tabs on the guy in the car beside mine. It looked like he

was smoking now. Possibly smoking weed. I was a bit un-nerved. I would need to

stop soon and I really hoped the guy would be away before I had to stop. I

would make sure that Dermot was around for the stop. I finished my bottle, and

tried to stretch out the time when I was riding with no liquid (less weight) –

it had become a balance – usually I could do an extra two laps with an empty

bottle before needing to drink. It was time to stop. The guy was still there,

fast asleep in his car. Weird. He didn’t wake up when we stopped. Again I

replenished and re-fuelled, and re-did the suncream. My bowels weren’t

demanding evacuation, so if I did need to go, I’d be going solo. Dermot was

probably relieved. We took a couple of quick photos of the two of us at the

car, and I got back to it. I hadn’t photographed the road art yet, and I said I

would leave it until three-quarters distance.

I hoped the guy in the car would leave before Dermot headed off. A couple of laps more and it would be time for Dermot to go. It had been good. He had taken care of the traffic, shouting “clear” to me at the top when I was turning, moving out slightly in the road to keep cars behind when it was less safe to overtake, and just generally having someone there took away some of the stress of feeling a bit vulnerable. Anyway, Dermot had to go. We got to the top. “Stay safe”, he said. “65”, I shouted back. 65 laps complete. Over two-thirds of the way there. It was just before 4pm. 11 hours done. If I finished the Everest altitude, and I was becoming increasingly confident that I would, then I should be done by around 9:30pm. I expected it to get dark just after 10pm. If I wanted to complete the 10,000 metres, then it would be approaching midnight before I would be done. Of the limited knowledge I have of people who have done it, they have all said that the time between 8848m and 10,000m is the toughest by far.

I

had to keep going. The first couple of laps after Sherpa Dermot (as Everesting

companions are called) left felt a bit quiet. I hoped that the guy in the car

would be gone before I had to stop again. I guessed if he meant any harm, I’d

have known about it by now. I was still feeling decent. I was amazed at my

consistency of power, heart rate and ascent/descent times. My ascent power was

holding at around 200 watts. My ascent heart rate was steady at 130-135bpm. My

descents were holding at about 2:15. The descent, tucked down low to an

aerodynamic position for greater speed, just started to get uncomfortable in my

arms as I was approaching the roundabout, so it was a good length of descent. I

was having to pee more often than I thought I would need to. But I didn’t want

to drink any less, as it all seemed to be going well and I didn’t want to

change anything. There had been a couple of hours when I didn’t pee at all in

the middle of the day, so I had upped my fluid intake a bit. My stomach still

felt OK – I was worried I might start feeling pukey.

The

guy in the car disappeared, thankfully. No harm was done to my car. I had

another stop after he left. It was becoming tougher to stand upright as my back

was crimping to the shape of the bike. But my legs felt OK. I did my usual at

the stop – ate, drank some flat Coke, topped everything up, re-applied the

suncream. Then I put my battery pack in my front frame pouch and connected it

to the Garmin. I’d tested this previously, but had a bit of a nervous moment

hoping it would connect without shutting the Garmin down. Thankfully it worked

as it should and it was all good. All done as efficiently as possible.

I

had wondered if I would make it through the day without needing the major

toilet stop. But then, it hit me. I thought maybe I could do a few more laps

and maybe the urge would disappear, but experience took over and told me that

the urge wouldn’t go away. I knew this was the time. I had to go. So I changed into

my trainers and took my bike and myself and my toilet roll and hand sanitiser

off into the woods. I moved a big branch and made a bit of a trench and did

what I had to do, as quickly as possible, and tried to bury it as quickly as

possible and get out of the woods as quickly as possible. Squatting was just

about possible, and it was good that I’d had the 5-10 minutes off the bike

immediately beforehand. Had I done another hour on the bike and then had the

urge, without having had 5-10 minutes off the bike, the whole operation would

have been made more difficult as squatting and standing back up would have been

difficult.

I

went back to the road and went to carry on, then I remembered I had hand

sanitiser and toilet roll in my back pocket, so I put them back in the car.

Then I remembered I had trainers on, and had to change into my bike shoes.

Slightly less clarity of thought at this stage perhaps… Then I got going again.

That had been my longest stop. My elapsed time was now 70 minutes slower than

my moving time. I could do 7 climbs in 70 minutes. I thought about how helpful

it would have been to have had a full-time supporter (or support team) by the

car. It would have removed all the worries about feeling isolated and

vulnerable and conspicuous, and it would have made me quicker – I’d have had to

carry much less food and drink on the bike and I could have shouted my “orders”

at them as I passed. I could also have left all my valuables (car keys, 2

mobile phones etc), and probably saved 2-3kg in weight. I also knew that I

weighed a bit more than I did a couple of months ago, so in total I was

carrying 6-7kg of “extra” weight.

There’s

an Everesting “calculator” online:

https://everesting.cc/app/lap-calculator/

My

Strava segment ID was 24864318 (but the descent was slightly longer than the

ascent as I went round the roundabout).

Playing

around with the numbers, 6-7 extra kilos seems to cost 20-30 seconds per climb,

or around 15 watts per climb. You might gain a fraction on the descent due to

being a bit heavier, but the extra weight was costing me 20 seconds x 95 climbs

= about half an hour. Small differences in lap time add up to big chunks over

the duration. But, it was what it was. And all that said, I quite liked the

idea of doing the ride “unsupported”, or largely unsupported.

I

remember seeing my Garmin reading 166 miles and noting that I was now in

uncharted “longest ever bike ride” territory. I still hadn’t managed to

photograph the “road art”. I’d tried a couple of times as I cycled over it, but

it came out blurred. I kept forgetting. Then the angle of the sun meant the

light was terrible. But it was just one photograph, surely I would get it?!

I

just kept going. I managed to get word to Deirdre that all was good and that I

hoped to complete by 9:30pm. We had talked about her cycling out. But this

would have meant her staying until the bitter end (whether that came at 10pm if

I decided I’d had enough, or midnight if I carried on to 10,000m). This wasn’t

realistic as being by herself on the hill in the dark wasn’t a good idea. So

she got a bus out, and would get the last bus home before dark. I’m sure she’d

have liked to have seen the “Everesting” moment, but it was what it was.

She

arrived at about 6 o’clock. I had been on the go for 13 hours. I had maybe

three and a half more hours to hit Everest. It felt close. Normally three and a

half hours is a long time on the bike, but looking ahead it didn’t feel like

all that long. OK, my back was getting pretty stiff and stuck in position by

now, but I still wasn’t fed up, or struggling. I was strong. My knees hadn’t

started getting painful, they were OK. The tendons weren’t 100%, but they were

doing well. I had done quite a bit of low-cadence, high-gear strength work in

training, and this was standing my in good stead, as the ascents were at low

cadence (less than 70rpm in parts, in my lowest gear). Maybe I could have put

lower gears on the bike, but 70rpm was just about OK. I had read about people

who ended up struggling to turn the pedals at all, lumbering at 40rpm and 3mph

before having to call it off. I was doing fine.

Again

it was nice to see someone. She was keen to take a few photos. She maybe didn’t

choose the best time, hanging out into the road as cars were passing in both

directions, and I didn’t want to lose time and momentum stopping to explain to

be careful and be inconspicuous. I passed her the car keys and tried to shout

what I could. She got into the car and watched a few laps. I was coming up to

another break so she was able to help with filling the bottles and sorting out

the food and finding the clothes I’d need, as it was getting cooler now and the

sun was dropping in the sky off to the north-west. I put on my gilet as it wasn’t

yet cold enough or dark enough for the full reflective warmer gear.

The ascents with the gilet on were a bit warm and sweaty, and I unzipped everything to get air flowing. I zipped up again for the cooler descents. Deirdre went for a walk up the hill and took a few more photos. By now it was clear that I would do this and I would have the strength to continue beyond 8848m. I had one quick stop before Deirdre headed off, and she captured on camera the agony of getting back onto the bike. While on the bike, I was OK. It was being in any position other than the cycling position that was tough!

In my mind, the next time I stopped would be having completed Everest and needing to change into my “night-time” gear. The sun disappeared at 8:40pm, but because it disappeared behind the hill it would be bright for another hour or so. I had to just get on with it.

By

now I wasn’t looking at how long each ascent or descent took, all that mattered

was the lap number. Because an ascent and a descent were counted as separate

laps on my computer, I had to divide the lap number by two. But I had missed

two or three presses of the Garmin on various laps, which meant some “tough”

mathematics: I had to add two or three to the lap number, and then divide by

two. When the number was 95, that was Everesting complete. I hit 90. 91. 92.

Still going well. But it was getting darker. I had to stop before I hit 95,

because I had to put on my reflective night-time gear and lights. Had I only

been targeting Everest and not the 10,000m, then I would have battered on to do

the 95 and would have finished just before dark without needing reflective gear

and lights. But I knew I was carrying on and so I may as well have been in the

reflective gear sooner rather than later.

This was quite a long stop as bending over to undress and re-dress was tough. But in the end I managed to layer up with a base layer, a high-vis jacket, a high-vis reflective bib (tightened in with safety pins to stop it flapping about), a hat, a reflective helmet, lights on the helmet, reflective leggings, gloves under my cycling gloves, clear glasses instead of sunglasses, and various reflective bands around my ankles and around various parts of the bike. And of course, lights on the bike. I couldn’t get the rear light on the setting I wanted, which I was annoyed about. I couldn’t figure it out and couldn’t afford to waste any more time on it. I had brought spare cycling shorts thinking I might change them an hour after the long toilet stop, but I never did and I couldn’t be bothered now. I ate, drank, and loaded up the bike with the food and drink I’d need to get me through the final 2-3 hours. I was ready for the darkness, and ready to carry on until 107 laps and 10,000 metres and 200 miles had all been hit.

Because

I had my gloves on, I couldn’t operate my phone as well, so I wasn’t able to

mark the Everesting moment with a photo or a video. I don’t even know when the

exact moment came. I had told myself I needed 95 laps to guarantee Everest so

at the top of the 95th lap I might have had a small smile to myself, I can’t

remember. It was about 9:40pm or so. 16 hours and 40 minutes in total, with

around 15 and a quarter hours of moving time. It was such an anti-climax. There

was still business to attend to. The goal was the 10,000 metres, which would be

another 12 laps, another 2 hours. I just powered on. It wasn’t totally dark

yet.

96 laps came. 97. The light dropped away rapidly. I never did get the photo of the “road art”. My front light has three brightness settings. The brightest setting drains the battery in 90 minutes. The dimmest setting lasts 6+ hours. 98 laps came. I didn’t like this. I had to be on the brakes the whole way down the descent. I was seeing bats flying madly, zooming out of the trees and over the road. They weren’t just small things either, they were big hefty beasts, flying at speed. And bats have teeth too. It wouldn’t be good to ride into a bat, I could end up needing a rabies injection in hospital. Other birds also seemed to be flapping about. Moths were being attracted to the lights and it was like riding into a snowstorm in places.

I started ascent 99. Animals were darting into the road and I nearly ran over something the size of a cat when it ran out in front of me. I didn’t want to think about hitting such a thing at speed… I dimmed the light to its dimmest setting on the ascent to save the battery. It wasn’t really bright enough, but it would do. I’d save the bright setting for the descent. It was very dark now. There was no light coming from anywhere. A car approached from behind and must have wondered what on earth was going on.

Descent number 99 wasn’t good. It was

so slow. On the brakes the whole time. It was almost as slow as the ascent,

which meant to complete 100 would take until well after midnight. I wasn’t sure

I wanted to be up there alone after midnight with all sorts of flying and

crawling animals zooming about my head and my wheels. It was tough to be on the

brakes now for most of the descent to keep my speed down, with my arms and

wrists getting sore. It was getting dangerous. It would have been great to have

had people at my own car, and a support car behind me with headlights and

hazard warning lights. I could have had a few more stops, stretched out my

back, shaken out my arms and shoulders, and taken my time, without having to

worry about feeling vulnerable.

There

was no way I was making 107 climbs. It was just too dangerous. I would be

really pushing my luck and based on what I had experiences on the few dark

ascents and descents I had done, I thought there was a good chance that

something bad might happen.

I

thought 100 would be a nice round number to end on, and I could then freewheel

into Haddington (just beyond the foot of the climb) where there would be

streetlights and where I could put in the handful of extra miles needed to

break 200 miles. I was disappointed, but there is no doubt it was the right

call. The 100th repeat was not enjoyable at all. I still had great legs, and my

consistency was still there, my strength was still there, but it just wasn’t a

place to be at 11pm in the dark, never mind trying to survive another 2 hours.

I wanted to make it home in my own car, in one piece. I had Everested. I could

easily have made the 10,000m (the hardest part would have been dealing with my

back which by now was getting pretty stiff and sore, as was my left shoulder).

I would manage to break 200 miles with circuit of Haddington under the street

lights. I’d had a good day with no mishaps. It wasn’t worth pushing my luck

with something that I knew was dangerous.

So

I tentatively descended at a very slow speed. It was pitch dark. I got to the

roundabout where there were streetlights, and looked back up the hill, and knew

I had made the right decision. I had 7 more climbs to go to make the 10,000m.

It would take me about another two hours, judging by the slow descent speeds,

and that was a best-case scenario assuming I didn’t hit a bat or a furry

critter and crash.

So

I pedalled gently into Haddington, and pedalled gently through Haddington and

urged the Garmin to hurry up and hit 200 miles. Finally it did. 200 miles. A

big day. I was a bit frustrated that the 30-ish minutes of easy pedalling

through Haddington meant my average power and heart rate dropped by a few watts

and a few beats per minute.

I

got to the roundabout and had to climb back up for a couple of minutes to the

car. It was black. “Like looking up the devil’s backside…” I got to the car at

just after 11pm and dismounted. Ride over. Again it was a little bit of an

anti-climax. There hadn’t been a “wow moment” where I’d overcome all the pain

and suffering to triumph. It hadn’t been like that.

I

had to stop my Garmin from recording, save the data and re-set it. This gave me

a bit of concern. It has frozen in the past when trying to save data, and this

was a particularly big data file. I didn’t want to lose the data. It took a

while, but it saved. Thank goodness.

I

didn’t dwell. I heard laughter and shouts in the distance. Local drunks. I

wanted out of there and off that hill as soon as possible. I took a quick photo

and loaded everything into the car as quickly as I could, threw on a jacket over my high-vis bib as I was worried about cooling down rapidly, fell into the

driver’s seat, and drove the few minutes into Haddington where I parked up

under the streetlights. I finally felt at ease. I’d come fairly strongly

through a long, long day, unscathed. Deirdre had left a bun of some description

in the front seat and I wolfed it down. I sent a couple of quick messages to

let people know I was finished safely.

Tiredness

was setting in quickly so I got on the road, wanting to get home as quickly as

possible. Pressing the clutch was difficult… I made it home and needed help

getting out of the car. I couldn’t get out unaided. I could barely stand

upright. I was moulded, crimped to the shape of a bike rider and couldn’t

comfortably get out of that position. I had great help getting everything back

up the stairs to the flat, and had a Tailwind recovery drink and some pizza (with ginger, for its anti-imflammatory properties). It

was good. I’d say I could have eaten a few pizzas. I needed help to undress,

and showering was so difficult. As was drying myself. It took ages. I just couldn't straighten up, nor bend over further than I had been bent over the bike.

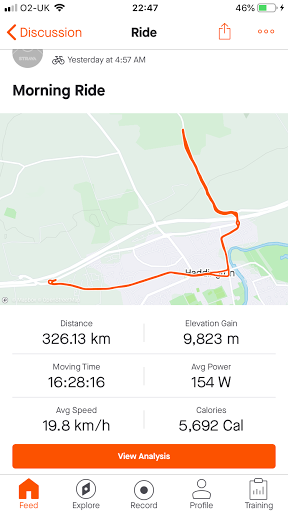

I

had a look at the Garmin statistics. 18:04 total time. 16:27 moving time.

326km. 202 miles. 19.8km/h average speed (12.3mph). 100 repeats. 78 rpm

average. 185 watts normalised power (very surprised how high this was: 2.8

watts per kilo), 157 watts average power (2.4 watts per kilo), 5700 calories

burned, and my Garmin said 32,227 feet climbed (9823m). However, I knew these

altitude readings were on the high side, and the actual ascent was just over

9500m (just over 31,600 feet). I calculated that it took me 153,972 pedal

strokes. I would upload the data the following day, and submit it to Hells 500

for verification.

Then it was time for bed. I had been awake for about 43 hours at this point. I never usually sleep well after a big endurance event, and this was no exception. The next day was a major tidy-up operation. I hadn’t actually eaten that much of the food I had brought, but that’s not to say I under-ate – I felt I ate more than enough on the day, and my stomach dealt with it fairly well. I hadn’t drank anywhere near the total amount of water I’d had in my car either, but again I drank what I needed and was constantly needing to pee. I hadn’t raced it, and so was probably sweating less than I’d be in a race, and I’d had the descents to recover. Interestingly, looking back on the data, my heart rate after over 2 minutes of descending and not pedalling wasn’t as low as I thought it would be and it rarely went under 100bpm.

I

was pretty slow for a few days afterwards as my back and left shoulder took

time to get used to being straight upright again. I often found myself sitting

crouched over as if on a bike, because this was the most comfortable way to

sit. But then I forced myself upright to help with getting my body back to

normal. In the immediate aftermath, I came out in a strange rash on my

shoulders and upper torso. I assumed it was just heat or sweat rash, and it

soon dissipated. Then a couple of days later it came back. It was bizarre. It

wasn’t shingles, like I’d got in the aftermath of my tough 2019 season, but it

was a weird rash. I kept an eye on it. I

didn’t feel sick or feverish or anything, and eventually after about a week it

subsided too.

I

uploaded the ride to Strava and had it approved by Hells 500 pretty quickly. I

went into the Everesting Hall Of Fame (online): https://everesting.cc/hall-of-fame/#/hill/3888975503

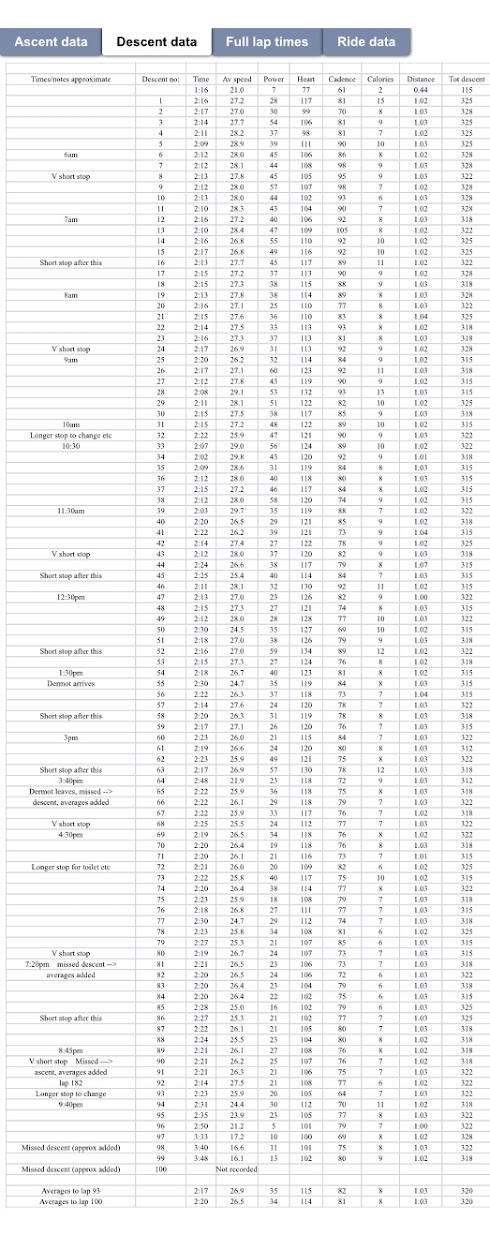

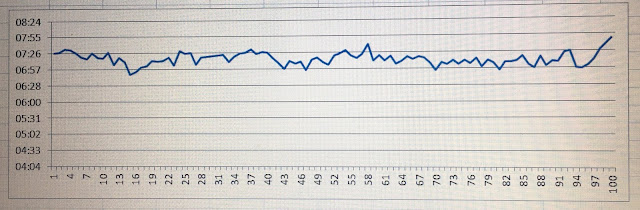

More ride data is below - a spreadsheet of all my ascent, descent and total lap data (I tried to make some notes outlining the major milestones and times in the first column of each, but these may not be totally accurate!), as well as some more graphs:

My average ascent time was 7:14, average ascent power was 198 watts, average ascent heart rate was 134bpm, average ascent cadence was 78rpm and average ascent calories burned was 48.

My average descent time was 2:19, average descent speed 27mph, and average descent heart rate was surprisingly high at 115bpm despite not pedalling...

Overall average lap time was 9:32. Nearly 6000 calories were burned in total.

My quickest ascent was 6:48 (8.2mph on lap 15), slowest was 7:48 (lap 100, 7.2mph).

My quickest descent was 2:02 (29.8mph, lap 34) and my slowest daylight descent was 2:48 (lap 64). My top speed was 65kph/40mph.

Highest average ascent power was 216 watts on lap 15 and 16, while my lowest average ascent power was 182 watts on lap 58, during the hottest part of the day.

Training Stress Score (TSS) is an interesting metric used by athletes to judge fatigue, and how hard they are training. TSS is a measure of the intensity and the duration of training. So, a hard hour of running will have a higher TSS than an easy 3 hours of cycling. At the Ironman world championship in Kona last year, my bike TSS was 216 and my run TSS was 183. I estimate my swim TSS would have been around 50. That gives a total Kona TSS of 450. My TSS for my Everesting ride was 562 - far in excess of the Kona TSS. Everesting probably felt a bit easier than an Ironman when actually doing it - I was getting repeated short recoveries during the Everesting, whereas in an Ironman you are pushing the whole time. However, in the aftermath of the Everesting, I felt much more fatigued than I thought I would, given how decent I felt when I was actually doing it. The very high TSS would explain this!

Just over 10,000 people have done an Everesting to date. In the approval email were links and images of the kit you could now buy. $200 jerseys and $150 shorts. Etc etc. Pricey. I wasn’t even that bothered about official approval. I knew what I’d done. That was enough.

My colleague Matt had managed to complete his Bob Graham Round in 23 and a half hours, managing to achieve membership of the exclusive sub-24 hour club. Good for him. It was an incredible feat. We had a socially-distanced meet-up to talk through the Everesting and the Bob Graham Round. I was glad that when I hadn’t slept and 3:30am came, that I knew that Matt also hadn’t slept and he had started 4 or 5 hours before me. I was glad we had arranged to have a meet-up afterwards. I had to have something to talk about!

During his attempt, he had reached the point of

being unsure if he would complete it. A group of 5 had started, which soon

became 2. It had looked like they might not complete it, then it looked like

they would complete it, but in more than 24 hours, then they made up good time

and got under the 24 hours. He usually makes video reports of his endeavours

and I can’t wait to see his report on this one. I bought him a custom-made “Bob

Graham Round <24” cap. It was good to chat with someone who “gets” endurance

sport. In the end it was difficult to say which was tougher. I doubt I could do

a Bob Graham Round. He doubted he could do an Everesting. Both are a bit

quirky, both are undoubtedly tough, both require fitness and mental stamina.

Anyone who does either is a strong person.